Welcome, bienvenue!

Greetings from UUEstrie, a liberal spiritual community that first gathered in the village of North Hatley back in 1886, as the First Universalist Church of North Hatley.

Salutations de l'UUEstrie, une communauté spirituelle libérale qui s'est rassemblée pour la première fois dans le village de North Hatley en 1886, sous le nom de Première Église Universaliste de North Hatley.

Join us Sundays at 10:30am for our weekly service.

Rejoignez-nous le dimanche à 10h30 pour notre service.

Our annual beginning-of-summer church picnic will take place at the home of Ryan Frizzell and Crystle Reid, which is in Val Joli, near Windsor QC. We shall gather at 11 am for a circle service near their pond. Email info@uuestrie.ca for the address or directions. Bring your own picnic or something to share with everybody. Friends and visitors are most welcome.

A retired professor from Champlain College in Lennoxville, Jan Draper recently spent a number of weeks in China, and will share some of her thoughts about her experience there. Service Leader: Camille Bouskéla.

~~~~~~

Professeur à la retraite du Champlain College de Lennoxville, Jan Draper a récemment passé plusieurs semaines en Chine et partagera avec nous certaines de ses réflexions sur son expérience. Responsable du service : Camille Bouskéla. Rafraîchissements : Phyllis Baxter.

Coffee Convenor: Phyllis Baxter

Charles Shields is a Canadian UU from Eastern Ontario who is also a member of the Board of the Canadian Unitarian Council. Each Board member of the CUC is a designated liaison with several CUC member congregations in the area of the country that they are from, and UUEstrie is on Charles’ list. Phyllis and Keith first met Charles at the Eastern Fall Gathering in Kingston last November.

Today, we celebrate Father’s Day, in traditional UU fashion. We welcome you to come forward with a photo, if you like, of your father, a father figure or a man whom you admire, and tell us a little about him.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Aujourd’hui, nous célébrons la fête des pères, à la mode UU traditionnelle. Nous vous invitons à nous présenter une photo, si vous voulez, de votre père, d’une figure paternelle ou d’un homme que vous admirez, et à nous en dire un peu plus sur lui

All are welcome! Small-group sharing and deep listening. This is the final meeting until next fall. (At this meeting, we will discuss the best evening of the week for our autumn schedule. If you would like to attend, but cannot, please let Rachel know what day(s) of the week are the best or the worst for you. Just reply to 16rg10@gmail.com. Thank you.)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Le partage et l’écoute profonde en groupe. Tous sont les bienvenus ! C’est la dernière réunion jusqu’à l’automne prochain. (Lors de cette réunion, nous discuterons de la meilleure soirée de la semaine pour notre horaire d’automne. Si vous souhaitez y assister mais ne le pouvez pas, veuillez informer Rachel des jours de la semaine qui sont les meilleurs ou les pires pour vous. Il suffit de répondre à 16rg10@gmail.com. Merci.)

Daniel Miller is a Religion prof at Bishops University. He recently gave a version of this talk down in Newport Vermont.

Our 3rd UU principle calls us to accept one another, and our 4th calls us to a free and responsible search for truth and meaning. So what is the problem?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Daniel Miller est professeur de religion à l’Université Bishops. Il a récemment donné une version de cette discussion à Newport dans le Vermont.

Notre 3ième principe unitarien-universaliste nous appelle à nous accepter les uns les autres et notre 4ième nous appelle à une recherche libre et responsable de la vérité et du sens. Alors quel est le problème?

We all face difficult choices in our lives. As a parent and advocate for her autistic son, Angela Leuck has had to make many gut-wrenching decisions relating to his health, education and security. Her experiences have led her to think deeply about the decision-making process. She will share some of her insights on how – in the face of uncertainty and imperfect knowledge – we can make life’s tough choices.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Nous sommes tous confrontés à des choix difficiles dans nos vies. En tant que parent et défenseur de son fils autiste, Angela Leuck a dû prendre de nombreuses décisions déchirantes en matière de santé, d’éducation et de sécurité. Ses expériences l’ont amenée à réfléchir profondément au processus décisionnel. Elle partagera certaines de ses idées sur la manière dont, face à l’incertitude et aux connaissances imparfaites, nous pouvons faire des choix difficiles.

Musician: Ryan Frizzell

In 2018, Amanda was diagnosed with placenta percreta, a complication during pregnancy which carries the risk of life-threatening hemorrhage during delivery. Amanda will share her experiences as well as reflect on the challenges women face during high-risk pregnancy.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

En 2018, Amanda a été diagnostiquée avec du placenta percreta, une complication pendant la grossesse qui comporte un risque d’hémorragie mettant en jeu le pronostic vital pendant l’accouchement. Amanda partagera ses expériences et réfléchira aux défis auxquels les femmes sont confrontées pendant leur grossesse à haut risque.

Musician: Ryan Frizzell (Trumpet) and Brian Herring (Organ)

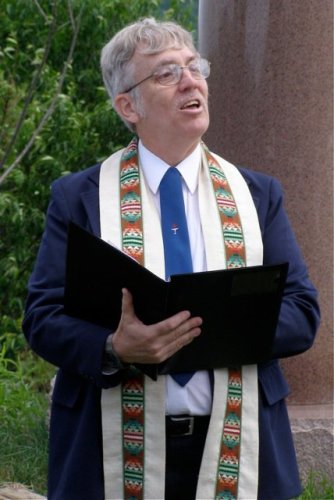

We welcome back for another visit the Reverend Brendan Hadash. Brendan was our minister in the 1980s, when we shared him with Derby Line and West Burke VT. Now retired from full time ministry, he continues to share a reflection in our worship service from time to time. This time he will reflect on the variations among UU congregations across Canada.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Nous accueillons de nouveau le révérend Hadash pour une autre visite. Brendan était notre ministre dans les années 1980, lorsque nous l’avons partagé avec Derby Line et West Burke VT. Maintenant à la retraite du ministère à temps plein, il continue de partager une réflexion dans notre service de culte de temps en temps. Cette fois, il réfléchira aux variations entre les congrégations UU à travers le Canada.

Musician: Mike Matheson

Spirit Circle. Thursday, May 9, at 7:15 p.m. Theme: Curiosity. All are welcome! Small-group sharing and deep listening.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Groupe de l’Esprit. Jeudi 9 mai à 19h15. Thème: Curiosité. Le partage et l’écoute profonde en groupe. Tous sont les bienvenus !